Evangelicals in Society and Politics: The Impacts of Their Growing Influence

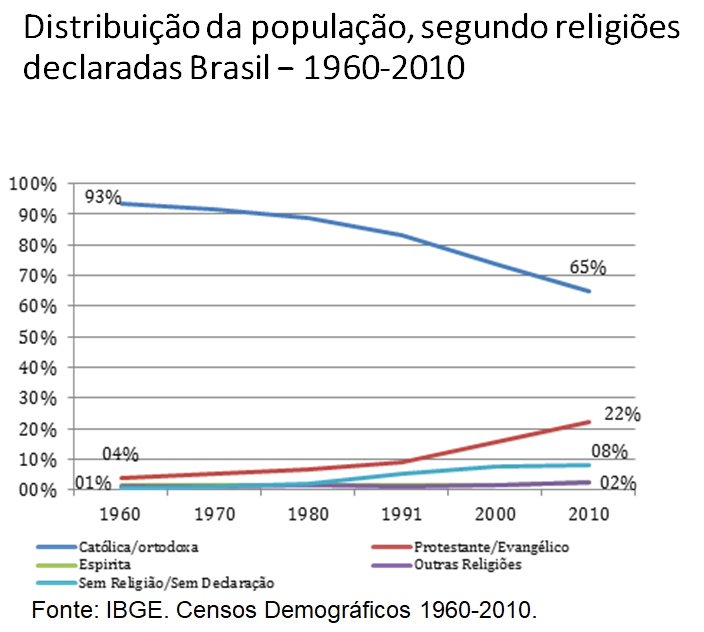

The 2010 Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) census found that Evangelicals and Protestants represented 22% of the Brazilian population. Today, they should be close to one-third of the country’s population, with Pentecostals leading the ongoing increase. At the same time, there is a decrease in the number of Brazilians who claim to be Catholic: in 2010, it was 65%, but this percentage should show a further drop in the census scheduled for 2020.

As they become more numerous on the impoverished outskirts of capital cities and metropolitan regions, in small and medium-sized towns in the countryside, and on the new agricultural frontiers of the North and Midwest, Evangelicals are becoming more politically active, not only in the running for legislative and executive positions at the three levels of government, but also in seeking to influence the political and social agenda on moral, behavioral, and even economic issues.

These were the main conclusions of the panel “Evangelicals in Society and Politics: The Impacts and Meanings of Their Growing Influence,” held at the FHC Foundation with the participation of two researchers who specialize in the topic.

“Today, it’s just not possible to reflect on Brazilian democracy without considering evangelical political activism. Gone are the days when they were outsiders in politics.”

Dr. Ricardo Mariano, Professor at the Department of Sociology of the University of São Paulo (USP) and Researcher of the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq)

Population distribution by voter-stated religion, Brazil – 1960-2010. Source: Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), 1960-2010 Demographic Censuses. Blue = Catholic/Orthodox, red = Protestant/Evangelical, green = Spiritism, purple = other religions, teal = voters with no religion or voter who did not state a religion.

“When will the two curves (above) meet? Some demographers expect this to happen in the mid-2030s, that is, in about 15 years.”

Dr. Ronaldo de Almeida, Professor at the Department of Anthropology of the State University of Campinas (UNICAMP) and Scientific Director of the Brazilian Center for Analysis and Planning (CEBRAP)

According to Dr. Almeida, author of “A Igreja Universal e seus demônios” (“The Universal Church of the Kingdom of God and Its Demons”- Terceiro Nome, 2009), in the early 2000s, it was thought that the growth of Evangelicals would hit a certain maximum number, but this trend has continued and has taken place in many layers of society and throughout the country, with predominance among the poorest, least educated, and non-Caucasian.

“There is a perception of acceleration of this movement in such a way that it is expected that in the 2020 census there will be an even closer approximation between the two lines. In the metropolitan area of Rio de Janeiro, there is already a balance between the Evangelical and Catholic populations. In the state of Rio de Janeiro as well as in Rondônia, Catholics already comprise less than 50% of the population,” he said.

Women ‘pull’ the conversions

The continuous expansion since the 1960s is due to “tireless, efficient, and vigorous proselytizing, also carried out by laypeople, especially women,” said Dr. Mariano, author of “Neopentecostais: sociologia do novo pentecostalismo no Brasil” (“Neopentecostals: sociology of the new Pentecostalism in Brazil” – Edições Loyola, 2018). “They are the ones who recruit and convert their husbands, children, neighbors, and co-workers,” he said.

The relative institutional weakness of Catholicism, due to the high proportion of non-practicing Catholics and the insufficient number of priests in Brazil, made it easier for the success of competitors: 44% of Evangelicals come from Catholicism, while 90% of Catholics were born in the church itself.

Moreover, according to the speakers, Pentecostal churches are more competent in addressing the needs and desires of the poorest sections of the population: they adapt the religious call to their material and cultural reality, offer spiritual, emotional, therapeutic and welfare support to their congregation, form community support and sociability networks and, by establishing well-defined moral and behavioral standards, contribute to improving the quality and standard of life of church members and their families.

‘New visual and auditory landscape’

“As we walk the streets of the poorer areas of cities and towns, we see large numbers of small churches, Bible verses written on the walls, groups of church members with the Bible under their arm, and we hear gospel music everywhere,” said Dr. Ronaldo de Almeida.

According to the organizer of the collection “Conservadorismos, fascismos e fundamentalismos: análises conjunturais” (“Conservatism, fascism and fundamentalism: conjunctural analysis” – UNICAMP Press, 2018, in partnership with Dr. Rodrigo Toniol), the growth of Pentecostalism is related to the perception of increased violence and the presence of organized crime in more impoverished regions, especially drug trafficking.

“Evangelical dynamism takes advantage of the increasingly widespread crime in the country (substituir link para o texto da segurança em inglês) because, to feel safer or even to move away from crime, many people seek refuge in evangelical churches, where they find meaning and identity for their or even a kind of safe conduct,” explained Professor Almeida, who was also a postdoctoral researcher at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales (Paris).

Religious domestication

Although there is no empirical evidence to prove that adherence to Pentecostalism results in improved income and quality of life for followers, the two speakers agreed that the conversion improves self-esteem and gives a new perspective on life and future.

“Many followers quit drinking, quit smoking, stop fighting with their wives, and take better care of their families. There is some religious domestication, which is no small feat,” said Professor Mariano.

Young people tend to get married early due to premarital sexual restrictions, and despite not always having enough education or income to form a family, they avoid getting involved in street problems. “There is a virtuousness in the bonds that are created between the brothers of faith because they help each other primarily, exchange work information and strengthen social ties,” he said.

Conservative wave

Although there is a diversity of opinion in the Evangelical universe as well, with some churches and pastors clearly positioning themselves in defense of human and minority rights, in partnership with nonreligious civil society entities, it is the more conservative Evangelicals who have set the tone in the political arena.

“There is diversity in the Evangelical world, with more leftist or progressive segments, but the most moralistic or conservative sectors are hegemonic and have been much more active from an electoral point of view. They actively participate in the current conservative wave, being constituents and constituted by it, sometimes in the background, sometimes as the leading actors of the conservatism we see today,” said Dr. Almeida.

Dr. Mariano recalled that at the Constitutional Assembly that drafted the 1988 Constitution, Evangelicals were already present, with a 32-member group. Since then, they have sought to increase their political influence based on a growing group of members of the two houses and new radio and TV concessions. In the process, they took control or created new parties, presided over parliamentary commissions and occupied ministries and departments. Currently, the Evangelical group has 90 federal deputies and 9 senators, as well as state deputies, councilors, mayors, and governors.

Decisive support

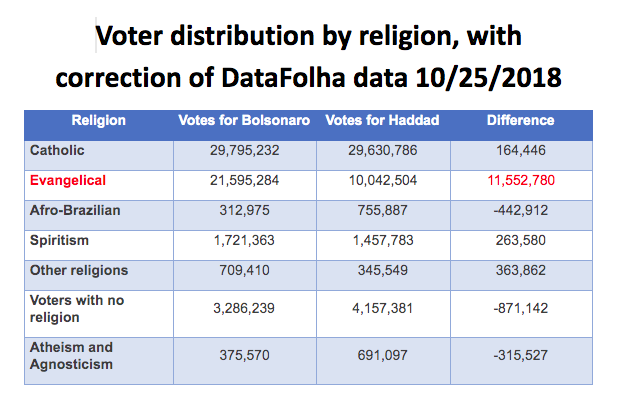

In 2018, Evangelicals provided decisive support to the election of Jair Bolsonaro to the Presidency of Brazil. Among Evangelicals, the Social Liberal Party (PSL) candidate got 11.5 million more votes than Fernando Haddad (Workers’ Party, PT). The difference between the two candidates in the second round was almost 11 million votes. See a table below, showing for whom supporters of different religions voted in last year’s elections.

“The political polarization that has occurred in recent years has helped to consolidate a Christian political right, a phenomenon well known in the United States, but which took decades to become a reality in Brazil,” said Dr. Ricardo Mariano.

According to the sociologist, the hard core of the anti-abortion, pro-traditional family, anti-feminist, and anti-LGBT Evangelical conservatism has expanded its interests to other areas, turning public schools and teaching materials into their battlefield. “Evangelical parliamentarians are the main proponents of the various ‘School Without Party’ projects in the federal, state, and municipal legislatures,” he said.

‘Prosperity Theology’

Evangelical leaders have also come to defend “right-wing” propositions in the criminal law field and more liberal ideas in the economy, for example by encouraging entrepreneurship on the part of its members, replacing a welfare system that has characterized the actions of the Catholic Church for many decades.

“This ‘prosperity theology’ abandons the old criticism of social inequality and reliance on God’s providence and values individual ascension by arguing that improving one’s life is religiously desirable,” said Dr. Ronaldo de Almeida.

According to the anthropologist, churches have been successful not only in elevating their members’ self-esteem and willingness to take the reins of their own lives, but have also organized courses on how to run a business, albeit informally, and “finally become their own bosses.”

According to the UNICAMP professor, the current rhetoric of this mostly conservative evangelical core is based on four “lines of force”:

1. Defense of morality and ethical and behavioral principles: according to the researcher, this would be the field in which evangelicals take the lead, in defending the prohibition of abortion even in the cases permitted by law today, criticizing sex education in schools and opposing ‘gender ideology’, same-sex marriage, and adoption of children by same-sex couples, among other issues that divide society.

2. Order appreciation speech: support for tougher measures against crime, such as hardening penalties, reducing the age of criminal responsibility, easing gun-control laws, etc.

3. Economics: defense of a less interventionist state in social and economic relations and less ‘welfare,’ valuing the idea of social ascension from the work itself and encouragement of individual and family entrepreneurship.

4. Betting on religious demonization and ideological and political polarization: exacerbation of criticism of other religions, especially those outside the Judeo-Christian tradition, and leftist parties and movements.

‘New Christian majority’

Dr. Almeida warned about the attempt to impose a public morality based on the idea of a ‘new Christian majority.’ “Although an Evangelical-Protestant majority is not yet a reality in Brazil, little by little, the more conservative and combative Pentecostal leaders are beginning to tap into the idea of Judeo-Christian majority supremacy that would include Catholics. Anyone who disagrees will be subject to the wishes of the majority,” he said, warning of the risk of this vision becoming hegemonic.

“Until recently, the effectiveness of this vast conservative-Evangelical agenda has been relatively limited, but its impact is already large in society and should increase, eventually obtaining important victories in setting legal normativity and public policies,” concluded Ricardo Mariano.

Otávio Dias is a journalist specializing in politics and international affairs, former correspondent of Folha de S. Paulo in London, and editor of the website estadao.com.br. He is currently the content editor at the FHC Foundation.

Portuguese to English translation by Melissa Harkin & Todd Harkin (Harkin Translations).