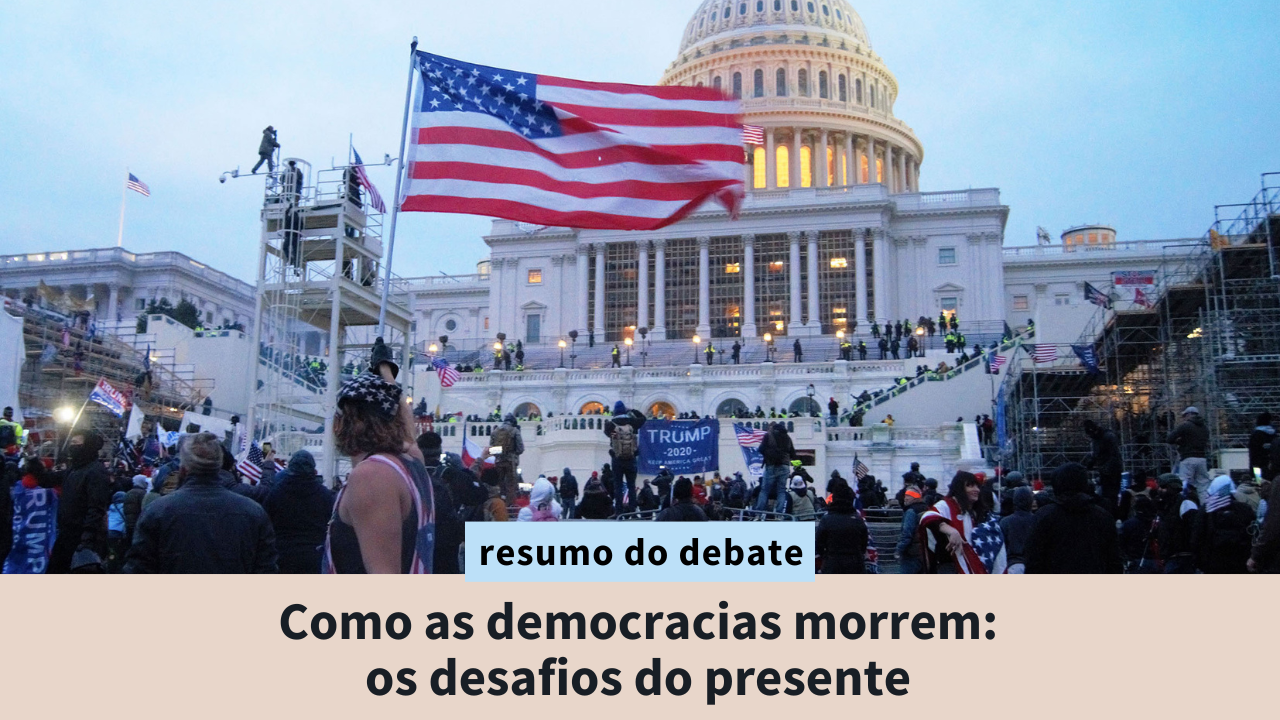

The FHC Foundation and the Network for Political Action for Sustainability (RAPS) held a meeting in which American political scientist Steven Levitsky — co-author of “How Democracies Die,” a best-selling book released in January 2018, in partnership with Daniel Ziblatt — chose to kick off with a touch of optimism by saying, “Although there is a consensus today that we are living in a time of global democratic decline, I believe that democracy has been surprisingly resilient in the 21st century.”

“According to the non-profit organization Freedom House, the world has been experiencing 16 consecutive years of democratic recession and authoritarian resurgence. But let’s look at the numbers. The European institute V-DEM has just published a report titled ‘Democracy at Dusk’?” which explains that, by the mid-2000s, there were 93 democracies in the world, while today, there are 89 democracies, only four fewer,” he said.

“Freedom House, however, sees a decline of 7 democracies in that period,It is significant, but there are more democracies today in the world than in the late 1980s, when, according to V-DEM, there were only 40 democracies on the planet. After the fall of the Berlin Wall (1989), that number rose to 60. In the year 2000, there were 87 democracies in the world. Today, there are 89. Therefore, we are still experiencing the most democratic period in the history of humanity,” said the Harvard University professor.

According to Levitsky, three factors explain this “remarkable democratic resilience:”

1. The democratic West is going through a period of low esteem, but it is not out of the game – “The US and Europe are still more attractive partners than Russia and China for many countries;”

2. A legitimate alternative to democracy has not yet emerged, unlike in the 1920s when communism and fascism seemed to be an alternative – “There is no Russian model that leaders and movements around the world are trying to copy, and many autocrats would love to replicate the Chinese development model, but that’s not easy;”

3. New autocracies suffer from the same weaknesses as the more recent democracies, such as corruption, crime, and unemployment – “When they do not solve these problems, they face popular discontent and fall.”

“For Latin Americans, for example, democracy is still the least bad alternative, or the lesser evil, as they say in the region. They do not like their political leaders, distrust democratic institutions, and like competitive elections in which they can not only choose their future president but also dismiss bad rulers from power. No other existing regime guarantees them this possibility,” said the political scientist.

“My optimism ends here because, in recent decades, autocrats, or autocratic candidates, have managed to come to power through democratic elections a lot more often, including in Latin America. These leaders are, in general, outsiders and/or populists who seek to mobilize portions of the population against the political system as a whole,” the speaker explained.

“Populism is not the only way democracies die, but it is becoming the leading cause of their death, especially in Latin America. That is not a new phenomenon in the region, but it is becoming prevalent,” Levitsky added. He also pointed out that in virtually all Latin American elections in the last four years, at least one of the finalists, if not both, were candidates who presented themselves as anti-establishment and/or populists.

“Not all recently elected Latin American rulers are populists, just as not all will attack democracy, but the pattern is clear: outsiders are defeating insiders across the region, and most of them are winning with a speech that targets the establishment. History shows us that we will have more institutional crises in the future,” he warned.

Is populism a threat to democracy?

Levitsky defined populism as an anti-elitist movement in which the leader—usually a charismatic personality who communicates in a simple and direct way—accuses politicians and traditional parties of being corrupt, oligarchic, and unrepresentative of the wishes of the people, promising to sweep them from the scene in the name of an authentic democracy.

According to the speaker, populist rulers almost always pose a threat to democracy for several reasons:

- They tend to be outsiders, and outsiders do not commit to the institutions of liberal democracy;

- Unlike professional politicians, accustomed to participating in negotiations and forming coalitions, populists do not have the patience to live with the premises of democracy, such as respecting the Legislative and Judiciary Powers, dealing with the opposition, civil society, and the media;

- During their campaigns, they promise to end a system they claim to be corrupt and unrepresentative because they are controlled by a political and economic elite insensitive to the needs of the people;

- In power, they realize that they will have to live with the institutions they have intensely criticized, and those institutions are generally controlled by a political, administrative, and legal elite formed during decades of work in the manner of traditional politics.

“By receiving a very radical mandate from the polls, populist leaders have a strong incentive to attack democratic institutions head-on, whether by trying to weaken Congress, change the composition of the courts, or even rewrite the Constitution,” he said.

With the support of the population, populists often win this confrontation and end up concentrating much power for an extended period: “We saw this with Perón, in Argentina (especially in the 1940s and 1950s); in Peru, with Fujimori (from 1990 to 2000); and with Chávez, in Venezuela (from 1999 to 2013).” Nicolás Maduro, Chávez's successor, is still in power today.

The supply of outsiders and populists is increasing in Latin America

According to Levitsky, the demand for populism in Latin America has long existed due to chronic social inequality, the gap between the elites and ordinary citizens, and, above all, due to the inability of the State to provide health, education, development, and ensure housing, transportation, and safety and security, among other essential tasks.

But according to him, what’s new is what’s happening on the supply side: “It’s much easier to be populist today than it was 40 or 50 years ago. And the reason is that political establishments, which had a moderating effect on politics, keeping the most radical ideas off the agenda, are weakening worldwide and in Latin America.”

Among the institutions of the political system that have suffered the most in recent decades, he highlighted three:

1. Political parties – “For decades, they functioned as gateways to politics, choosing and launching candidates, thus filtering outsiders and those most radical;”

2. Interest groups such as business associations and trade unions – “They have always been an important source of political, logistical, and financial support to candidates, whether right-wing or left-wing;”

3. The media, such as radio and TV stations and major newspapers – “Access to the media, which in the 20th century was restricted to some vehicles that had great power, has always been fundamental for candidates to reach voters.”

“I’m not Noam Chomsky, and I don’t think these organizations constitute a monolithic block. Even within the establishment, there is pluralism and competition. But, despite the differences, the establishment imposes some parameters for the exercise of policy, both in terms of substance and style. Politicians who violated these rules and crossed borders were generally poorly regarded by the establishment and became pariahs,” he said.

As they needed the support of the system or at least a considerable part of it, the politicians of the 20th century sought a balance between a greater appeal to voters, on the one hand, and an at least reasonable relationship with the establishment, on the other. “It wasn’t very democratic, but it’s how the democracies of the 20th century worked. But the days of this, say, establishment monopoly are over.”

In the United States, Europe, and Latin America, politicians no longer need the establishment and can raise funds online and reach voters via social media: “For some politicians, this represents a liberation, as they can break the rules of politics and present themselves to the population as a rebel who no longer depends on the elites and can do what is best for the people.”

The paradox of the 21st century: more democratic elections make democracy vulnerable

According to the political scientist, nowadays, anyone can win a presidential election, even if they have the entire political system against them: “It is simply much easier to bypass the establishment today than it was 50 years ago. That is undoubtedly democratizing, but at the same time, it makes democracy vulnerable to anti-systemic forces that may prove authoritarian.”

As an example, he recalled the case of the current president of Peru, Pedro Castillo, elected in 2021 in a very contested election. “Castillo, who was a candidate from outside the system, almost unknown, had the entire establishment against him. Businesspeople, the political elite, the media, and even the inhabitants of the capital city, Lima, mainly voted against him. But he won the votes of the poorest inland inhabitants and took office despite all the resistance. Perhaps they were the most democratic elections in the history of Peru,” he said.

“The days of democracy monitored by the political, intellectual, and economic elite are over. This process will not be reversed. Therefore, we will see more Trumps, more Bolsonaros, more Bukeles (reference to Nayib Bukele, president of El Salvador), and more Castillos. How democracy will sustain itself in this new populist and anti-establishment era is what all of us, political scientists, want to find out,” he concluded.

New generations of politicians need to raise the bar of politics

“What message would you like to convey to people who intend to run for office, especially the youngest?” asked political scientist Monica Sodré, executive director of RAPS, at the end of the webinar.

“It takes a sense of urgency. In the United States, where I live, and in Brazil, if we behave as if we lived in normal times, the consequence will be the loss of our democracy. To be a political leader in a period when democracy is threatened, one must have courage and think about the future. This is the time to make sacrifices and make political commitments that may not be as good individually or for my group in the short term, with the greater goal of preserving democracy in the medium and long term,” he said.

As an example of a policy that has demonstrated such courage, he cited Congresswoman Liz Cheney, who runs the risk of not being reelected due to her firm opposition to former President Donald Trump in both the US Congress and the Republican Party.

“It is also necessary to be fully aware of the degree of dissatisfaction of citizens with democratic institutions, of distrust towards politicians. In the US and Brazil, the legitimacy of the entire political system is hanging by a thread. Therefore, those entering politics have a heavy burden on their shoulders. If you continue to do what the politicians who preceded you used to do, if you lie to the voters, if you accept bribes, I repeat: we will lose our democracy. Younger politicians must raise the bar of politics,” he warned.

Otávio Dias is the content editor at Fundação FHC. He is a political and international affairs journalist, former correspondent of Folha de São Paulo in London, and former editor of the estadao.com.br website.

Portuguese to English translation by Melissa Harkin, CT and Todd Harkin – Harkin Translations.