Biography

At the end of the 1970s, with the beginning of the country’s re-democratization, he decided to enter politics. He was a Senator of the Republic, Minister of Foreign Affairs and Finance, and President of the Republic for two consecutive terms.

Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s complete Curriculum-vitae Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s complete bibliographyHe was born in Rio de Janeiro on June 18, 1931, into a military family. In 1953, he married Ruth Corrêa Leite Cardoso (1930-2008), with whom he had three children. He graduated in Sociology from the Universidade de São Paulo (USP), where he became a professor in 1953, and also obtained his doctorate and “livre docência” degrees.

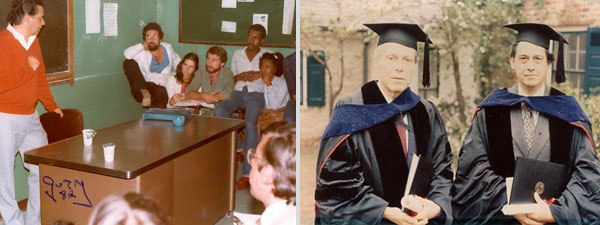

Involved in the struggle to improve public education and to modernize universities, Fernando Henrique Cardoso was threatened after the 1964 coup and decided to go into exile with his family in Chile and France in the following years. In 1968, he returned to Brazil and took up the Chair of Political Science at the Universidade de São Paulo (USP). In 1969, aged just 38, he was compulsorily retired and had his political rights revoked by Institutional Act No. 5.

In 1969, he founded the Centro Brasileiro de Análise e Planejamento (Cebrap) in São Paulo with other intellectuals who had been imprisoned by the military regime, which would become an important center for research and reflection on Brazilian reality. Furthermore, he taught at universities in the United States (Princeton University and the University of California, Berkeley) and Europe (Sorbonne Université and the University of Cambridge).

In lectures and articles published in various press organizations, he stood out as a critic of the military dictatorship and an advocate of a peaceful transition to democracy. Between 2003 and 2021, after leaving the presidency, he wrote monthly columns for the newspapers O Globo and O Estado de S.Paulo.

The intellectual

In addition to the Universidade de São Paulo, where he is professor emeritus, Fernando Henrique Cardoso has taught at renowned universities such as the Universidad de Santiago, in Chile; Stanford University and the University of California, Berkeley, on the East Coast; Brown University, on the West Coast; the University of Cambridge, in England; and the Université Paris Nanterre, École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and Collège de France, in France. He was president of the International Sociological Association (1982-1986). He has received honorary doctorates from more than 20 of the most prestigious universities. He was a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

His books have been published in Brazil and abroad. The set of his pronouncements and speeches as President of the Republic, delivered on the radio program ‘Palavra do Presidente’, was published in sixteen volumes by the Secretariat of Communication of the Presidency of the Republic (Brasília, 2002). He wrote articles in periodicals in various countries. In Brazil, he collaborated with the magazines Anhembi, Brasiliense, Novos Estudos Cebrap, and Revista USP, among others.

In 2005, he was named one of the 100 greatest public intellectuals in the world in a survey by the British magazine Prospect. In 2012, he was awarded the John W. Kluge Prize by the US Library of Congress, which honors outstanding achievements in the humanities. FHC was chosen for being one of the leading scholars of political economy in recent Latin American history.

For an overview of the documents held by the Foundation, click here to access the Guide to Fernando Henrique Cardoso Archive.

The politician

By invitation of Ulysses Guimarães, president of the MDB, in 1974 he coordinated the drafting of the electoral platform of what was then the only opposition party to the military regime. In 1978 he ran for the Senate as a candidate for the MDB, came in second place and became an alternate for Franco Montoro. In 1983, when Montoro was elected governor of São Paulo, he took his seat in the Federal Senate for São Paulo. In 1984, he played a leading role in the Diretas Já! (Direct Elections Now) campaign and in the organization of the successful candidacy of Tancredo Neves and José Sarney (Vice President) to the Planalto Palace, which meant the end of the military regime the following year.

Nominated head of government in the Senate by Tancredo, he was confirmed in office by José Sarney, who assumed the presidency when the politician from Minas Gerais fell ill on the eve of his inauguration and died a few weeks later. In this position, he articulated political and electoral reforms that paved the way for the redemocratization of the country, which ended in 1989 with the return of direct elections for president.

In 1985, he ran for mayor of São Paulo and lost by 30,000 votes to former president Jânio Quadros (PTB). The following year, he was reelected senator for São Paulo with 6 million votes, the second-highest vote in the state in a majoritarian election. He was the leader of PMDB in the Senate and one of the proposers of the 1987-88 National Constituent Assembly.At the end of 1988, dissatisfied with the direction chosen by PMDB both in national politics and in São Paulo, he decided to found the Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira (PSDB), alongside Mario Covas, Franco Montoro, José Serra, and other social democratic political leaders.

After the impeachment of President Fernando Collor de Mello in October 1992, he assumed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Itamar Franco’s government. In May 1993, following a call from the president, he moved to the Ministry of Finance. At the time, inflation was running at around 30% a month, the population’s purchasing power was decreasing daily, and the Brazilian economy was a cause for great concern.

Contrary to the opinion of those who thought it would only be possible to tackle inflation once a new government was in place, Fernando Henrique Cardoso brought together a team of leading economists and drew up a sophisticated stabilization plan, the Plano Real, launched in 1994. This included a major effort to reduce the fiscal deficit and a monetary reform, with the introduction of the URV, culminating in the entry into circulation of a new currency, the Real, in July 1994.

Although he was not an economist, Fernando Henrique Cardoso took on the role of explaining the Plano Real step by step to the population, as well as the political articulation for the approval of fundamental measures for the stabilization of the economy by the National Congress. In April 1994, he left the Ministry of Finance to run for President in a coalition formed by his party, the PSDB, the Partido da Frente Liberal (PFL), and the Partido Trabalhista Brasileiro (PTB). On October 3, he was elected president in the first round, with 54.3% of the vote. He took office on January 1, 1995.

In the Palácio do Planalto

Low inflation, modernization of the economy, strengthening of the state as a market regulator and promoter of social policies, consolidation of democracy – these were the main objectives of Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s two terms as President of the Republic.

The Fernando Henrique Cardoso administration’s reforms boosted the modernization of economic infrastructure, opening up private investment in the telecommunications, electricity, oil, transport and mining sectors. Independent agencies were created to regulate these sectors. Petrobras became a public corporation, controlled by the state but subject to competition with companies. The end of the monopoly strengthened the company.

The Central Bank gained operational autonomy to promote the reorganization of the public and private financial system, part of which was not prepared to live in a country with low inflation.

The federal government took on the debts of states and municipalities in return for a fiscal adjustment program that led them to join a concerted effort to reorganize public finances, which was indispensable for consolidating the stability of the economy. The Fiscal Responsibility Law established the general rules for a sustainable fiscal regime. Social Security, which was unbalanced, underwent a reform that mitigated the system’s tendency to run deficits.

Social policy also underwent important transformations, made possible by the end of high, chronic and growing inflation. The SUS came off the drawing board, primary education became education for all in fact, and social assistance programs became state policies rather than the charity of the government on duty. For the first time, a large-scale agrarian reform program was adopted. The ‘Comunidade Solidária’ program engaged civil society in local development programs, stimulated by the government, but without political tutelage and clientelist practices.

With its credibility restored by the stabilization of the economy, Brazil projected itself on the international stage. It normalized its relations with international creditors (disturbed since the moratorium of the previous decade), signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, led the peace agreement between Peru and Ecuador, promoted the South American Infrastructure Integration Initiative. It asserted itself as a democratic country, open to the world, politically and economically more predictable, aware of its regional leadership and willing to use it in favor of democracy and integration.

The stabilization of the economy, with the containment of the inflationary process, allowed the average income of workers to grow. However, successive international crises, structural changes in the economy and high interest rates prevented higher growth. In this context, unemployment and informality grew, especially in the main cities. Even so, poverty has been reduced considerably, thanks to the long-lasting fall in inflation and the government’s social policies, including the increase in the minimum wage.

For the positive evolution of Brazil’s social indicators during his time in office, Fernando Henrique Cardoso was awarded the “Mahbub ul Haq Award for Outstanding Contribution to Human Development” by the United Nations in 2002.

The consolidation of democracy was achieved with the recognition of human rights violations during the dictatorship, the creation of the Ministry of Defense under civilian command, and the peaceful transition to the government of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, the president elected by the opposition to the Fernando Henrique Cardoso government. Democracy was also an important element of Brazil’s foreign policy, exemplified by the inclusion of the “democracy clause” among the legal commitments made by Mercosur member countries.