Thirty Years of the Real Plan: Memories, lessons learned, and challenges

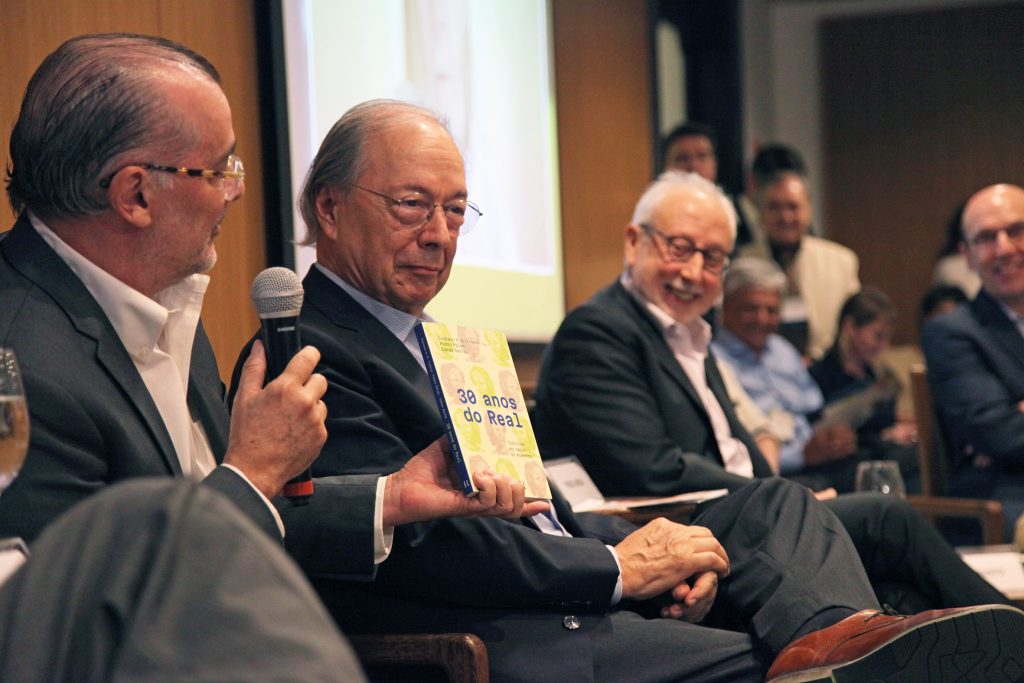

A debate marking the 30th anniversary of the Plano Real (Real Plan) brought together key economists who played pivotal roles in creating and implementing the new currency, along with Ambassador and former Finance Minister Rubens Ricupero.

With a 30th anniversary on July 1, 2024, the Real Plan was a groundbreaking intellectual, economic, and political achievement. Its success was largely due to the unique dual expertise of then-Finance Minister Fernando Henrique Cardoso (1993–94, fondly remembered as FHC), who seamlessly combined intellectual insight with political acumen. By vanquishing the rampant inflation that had gripped Brazil since the early 1980s, FHC won the 1994 presidential election. During his two terms (1995–2002), he spearheaded reforms and policies that strengthened the real and modernized Brazil’s economy. However, new momentum is needed for the country to fully realize its potential.

“These two qualities rarely converge in one individual. As an intellectual, FHC assembled a team of economists, many of whom had collaborated for years at the Pontifical Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro (PUC-Rio), to devise an entirely original plan—something unprecedented worldwide. He grasped the plan’s intricate details and chose to fully endorse it,” explained Pérsio Arida, one of the architects of the Real Plan.

“As a politician, he successfully persuaded President Itamar Franco, negotiated with the Brazilian Congress, and communicated the plan to the public, securing the crucial support needed for its implementation. Having a good idea is one thing, but finding someone to make it a reality is just as important,” noted the former president of the Brazilian Bank of Economic and Social Development (BNDES; 1993–95), who assumed leadership of the Central Bank when FHC took office.

On June 24, the Fundação FHC hosted a debate to mark the 30th anniversary of the Real Plan, bringing together five economists instrumental in its creation and implementation alongside Ambassador Rubens Ricupero. Mr. Ricupero faced the challenging task of leading the Ministry of Finance in March 1994 when FHC stepped down to run for the presidency. Economist André Lara Resende, one of the key architects of the plan, was invited but could not attend as the date coincided with his mother’s seventh-day memorial mass.

At the event, the speakers reflected on some of the major challenges they encountered in Brasília after being called by FHC, shared behind-the-scenes insights into the plan’s implementation, and offered a “glass half full, half empty” assessment of the current state of the Brazilian economy.

The ‘half-full, half-empty glass’ of the Brazilian economy

“What worked, and what didn’t? Hyperinflation is a thing of the past, and after 1999, with the adoption of the so-called economic tripod, the balance of payments crisis also became history. But why didn’t the success of stabilization lead to accelerated growth in the Brazilian economy?” questioned Edmar Bacha, who chaired the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in 1995.

“It’s tough. Few countries have managed to overcome the middle-income trap since the Second World War. Those that did had much better income distribution, more efficient states, and were more open to the world. To reach a higher level of development, we face these three challenges,” Mr. Bacha explained.

“In addition to 30 years of the real, we’ve had over 25 years of the floating exchange rate regime, 25 years of the inflation-targeting system, and 24 years of the Fiscal Responsibility Act. There’s much to celebrate, but we still have a lot to tackle, such as low economic growth and high income inequality. Why is it so difficult to push through reforms in Brazil?” asked Pedro Malan, finance minister from the beginning to the end of the FHC administration.

“I’m struck by the interest the country is showing on the 30th anniversary of the Real Plan. This wasn’t the case on the 25th, 20th, or even the 10th anniversary. Perhaps it’s the unease about the present or the future that’s driving Brazilians to understand what was so unique about the Real Plan—that it achieved the near-impossible: the defeat of hyperinflation,” said Gustavo Franco, president of Brazil’s Central Bank from 1997 to 1999.

According to Mr. Franco, Brazil’s inflationary process during the 1980s and 90s was staggering: “We experienced 15 years of inflation, with a monthly average of 16%. It’s impossible to maintain a rational economic life in that kind of environment.”

“When I was invited to lead the Central Bank in March 1999, the government already sensed that the managed exchange rate—or exchange rate anchor—had run its course. At that time, interest rates managed the balance of payments while the exchange rate controlled inflation. We decided to reverse those roles: allowing the exchange rate to float to improve the balance of payments while implementing inflation targets,” recalled Armínio Fraga, who helmed the Central Bank for nearly all of FHC’s second term.

“The so-called ‘economic tripod’ emerged, consisting of a floating exchange rate, inflation targets, and fiscal responsibility. The structural reforms passed during the first term, including the reorganization of state finances and the privatization of state banks, provided a solid foundation for the tripod,” said Mr. Fraga.

“At the end of 2002, during the transition from the FHC administration to the Lula administration, there was a moment of stress, but fortunately, President Lula upheld the tripod. It proved resilient and, despite some challenges, remains in place today,” Mr. Fraga continued.

“The Real Plan altered Brazil’s trajectory by convincing the Brazilian people of the dangers of inflation. I’m less sure about the politicians. Thirty years later, many still deny the link between inflation and excessive public spending. They fail to see the connection between cause and effect. In recent years, fiscal responsibility has been abandoned, jeopardizing the economic tripod,” warned Rubens Ricupero, finance minister from March to September 1994.

How the ideas behind the Real Plan took shape

The most successful stabilization plan in Brazil’s history originated in the Economics Department of PUC-RJ in the 1980s, where a group of economists sought to understand the unique characteristics of Brazil’s inflationary process. “The idea that someone had a stroke of genius in isolation is completely false. It was a collective effort,” recalled Pérsio Arida, a professor at PUC-RJ during that time.

“In Brazil, inflation behaved very differently from other known inflationary processes due to compulsory indexation by law, which created a certain complacency about long-term inflation. While it was believed that indexation would cushion the effects of inflation, it was actually the serpent’s egg,” Arida explained.

“The Real Plan was conceived much earlier, through at least a decade of academic discussions at PUC-RJ on how to address the issues of persistent, high, and growing inflation. In 1984, André Lara Resende published the article ‘The Indexed Currency: A Proposal to Eliminate Inertial Inflation.’ That same year, he and Pérsio Arida launched the Larida Proposal,” noted Pedro Malan.

“Gradually, in the protected academic environment of PUC-RJ, a consensus emerged that Brazil’s chronic inflation needed to be tackled by addressing over-indexation, culminating in the idea of creating a single index, which would eventually become a currency,” Mr. Arida continued. Ten years later, on March 1, 1994, the Unidade Real de Valor (Real Unit of Value – URV) was introduced, serving as an embryonic currency designed to ensure a smooth and transparent transition from the cruzeiro real (CR) to the real.

The URV, the precursor to the real, was adjusted daily. While its value remained stable, the amount of cruzeiros reais equivalent to one URV fluctuated. Salaries denominated in URV were recalculated daily based on the prices of goods and services, which were also listed in URV but paid in cruzeiros reais. This synchronization of wages and prices around a stable reference—the URV—helped stabilize the economy. On June 30, 1994, as announced over a month prior, the Central Bank set the conversion rate at CR$2,750 per URV. The following day, on July 1, 1994, one URV was converted into one real (R$1), and the URV ceased to exist, having fulfilled its purpose.

The URV made it possible to end indexation without resorting to price and wage freezes. Previous plans had shown that freezing only temporarily impacted inflation, caused economic disruption, and led to legal disputes that became additional burdens on public finances.

By promising not to impose sudden shocks on the economy, the government eliminated the fear of an overnight price freeze, which had previously fueled inflationary expectations. In essence, the Real Plan broke inflationary inertia—the tendency for past inflation to carry over into the present—and stopped the preemptive behavior of economic agents who raised prices prematurely, fearing they would be frozen in the future.

“The lessons Brazil learned from earlier stabilization plans—such as Cruzado 1 and 2, Bresser, Verão, and Collor 1 and 2—were crucial to the success of the Real Plan. From the day Fernando Henrique was appointed finance minister on April 19, 1993, until the launch of the URV, 280 days passed. Adding the 120 days until the launch of the real, those 400 days changed Brazil,” recalled Mr. Malan, who took over the Central Bank in September 1993 during the Itamar Franco administration and, on January 1, 1995, became the sole finance minister of the FHC administration.

In June 1994, the final month of the cruzeiro real, inflation was 46.6% (which, if annualized, would have reached 9,785%). By July, the first month of the real, inflation had dropped to 6.76%. Over the first twelve months of the new currency, cumulative inflation stood at 33%. By early 1997, annual inflation had fallen below 10%, and by 1998, it was just 1.6%. The real, still in use today, has since allowed inflation to remain within a “civilized” range of 3% to 6% per year, with only a few brief periods where it surpassed 10%.

The Real Plan: A project to modernize Brazil

“Which political conditions made the Real Plan possible? Could it be implemented today?” asked Edmar Bacha. According to the economist, the stabilization plan launched during the Itamar Franco administration by the team of Finance Minister Fernando Henrique Cardoso had crucial support from Congress, which was essential for the approval of a series of measures before, during, and after its implementation.

“Firstly, there was fear among society and the political class that Mr. Lula, then seen as too far to the left, would win the 1994 presidential election. The Workers’ Party (PT) candidate was the clear favorite in public opinion polls at the time. Secondly, politicians realized that whoever managed to control inflation would have a strong chance of being elected president, and those aligned with them would share in the power,” Mr. Bacha explained.

“Finally, Fernando Henrique’s ability to neutralize opposition from Itamar Franco’s inner circle was key. There were moments during the introduction of the URV when some close to the president wanted to index wages at their peak, and during the transition to the real, they called for a wage freeze,” continued Mr. Bacha, the former Central Bank president.

He also pointed out that for the Real Plan to move forward, the government needed unanimous support from three parties: the Brazilian Social Democracy Party (PSDB), the Liberal Front Party (PFL), and the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party (PMDB). “The negotiations, therefore, involved the PMDB, represented at the time by Federal Deputy Nelson Jobim, who is here today. It’s important to recognize that Mr. Jobim supported the plan from the very beginning. If negotiations were to take place today, it would be with the Centrão (Big Center, a group of smaller centrist and center-right parties), which would undoubtedly be far more challenging,” he added.

According to Mr. Bacha, thirty years later, it would be far more difficult to secure parliamentary support for a 20% reduction in compulsory federal spending, as was achieved in the months leading up to the Real Plan. “Today, Congress holds more power, parliamentary amendments are at an all-time high, and the budget is even tighter,” he explained.

Mr. Malan recalled that the Real Plan was a stabilization program built on three pillars, established at the end of 1993: fiscal balance for the 1994-95 biennium, which required spending cuts, a series of constitutional amendments, and monetary reform centered on the URV. “Once the veil of inflation was lifted, other underlying issues became visible, such as the need for comprehensive reform of the national financial system, resolving state and municipal debts, ending state monopolies like Petrobras, and pursuing privatizations in sectors like electricity and telecommunications,” he explained.

“Defeating hyperinflation wasn’t the ultimate goal. Over the next eight years, we focused on consolidating the new currency, the real, and implementing the necessary reforms to modernize the country,” the former finance minister added.

“If it hadn’t been for the determination of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso after he ascended the ramp of the Planalto Palace in January 1995, it would have been impossible to approve the nine constitutional amendments that enabled the privatizations in the telecommunications, electricity, and mining sectors. This broad program of dismantling monopolies and privatizations was crucial for the consolidation of the real,” said Ms. Elena Landau, director of the National Privatization Program during the FHC administration. She was in the audience and was invited to join the discussion by Sergio Fausto, director of the Fundação FHC.

Gustavo Franco emphasized the strengthening of the Central Bank during the implementation of the Real Plan. “The Central Bank was created in the 1950s as part of the Bretton Woods Agreements (1944), but it was controlled by the National Monetary Council (CMN). The CMN was far more powerful than the Central Bank and included representatives from the private sector and non-economic ministries. As a result, the Central Bank had little authority to set the parameters for managing the national currency,” explained the former Central Bank president.

“During the Real Plan, we reduced the CMN to just three members, representing the economic ministries and the Central Bank. We also established the Monetary Policy Committee (COPOM), the Central Bank’s body composed of its president and directors, which sets the economy’s basic interest rate every 45 days. Additionally, we restructured the institutionality of the Central Bank, a reform that should have been made in the 1950s,” Mr. Franco continued.

“The FHC administration was characterized by a remarkable series of economic and structural state reforms. The Real Plan was far more than a stabilization plan; it was a comprehensive project to modernize the country,” added Mr. Arida.

Behind the scenes of the Real Plan

“President Itamar Franco was a complex figure—both indispensable to and the biggest obstacle to the success of the Real Plan. He wanted to stabilize the Brazilian economy and pursued this goal relentlessly until he met Fernando Henrique, his fourth Finance Minister. I was the fifth,” said Rubens Ricupero, FHC’s successor at the Ministry of Finance. After Mr. Ricupero, Ciro Gomes followed.

“Itamar saw the Cruzado Plan (from Sarney’s administration) as a reference point, which is why he wanted to incorporate elements into the Real Plan that FHC and the economic team refused to accept. Along with freezing prices, he wanted to fix interest rates and offer raises and other benefits to civil servants. Yet, despite all this, Itamar had one redeeming quality: he knew how to listen. And despite his eccentricities, in just two years and three months in office, he managed to resolve two of the military regime’s most challenging legacies—hyperinflation and the foreign debt crisis. He also saw Mr. Fernando Henrique elected in the first round in October 1994, which is no small feat,” said the ambassador.

“My role as FHC’s successor at the Treasury was to defend the economic team at all costs, and that’s exactly what I did. Nobody left. I was captivated by that team; there was no sense of hierarchy, and everyone enjoyed great autonomy, freedom, and intellectual maturity,” Mr. Ricupero added.

According to Mr. Ricupero, there was considerable debate but little certainty during the economic team’s meetings. “I didn’t attend all the meetings because, as Finance Minister, I had other commitments. Ambassador Sergio Amaral (who passed away in 2023) often represented me. But when I was there, I was somewhat alarmed by the level of uncertainty in the decisions that had to be made. Even the launch date of the real was heavily debated. Mr. André and Mr. Pérsio questioned whether the transition period from the URV to the real had been long enough. It felt as if they were daring young trapeze artists, launching themselves without a safety net,” he recalled.

The real and democracy

At the conclusion of the debate, Mr. Pérsio Arida emphasized that the real, Brazil’s currency, is a triumph of Brazilian democracy. This democracy began in 1985 with the election of Tancredo Neves and José Sarney in the Electoral College, marking the end of the military regime. It gained momentum with the 1988 promulgation of the new Federal Constitution and was solidified by the return of direct presidential elections in 1989.

“Created in 1993, the real is now a public good, and its true foundation is democracy itself. With elections approaching in four years, any leader who neglects inflation—an issue that deeply affects the people—will face consequences at the ballot box. Thus, the real’s survival is guaranteed by the democratic system,” said Mr. Arida.

“My colleagues argue that democracy is the real’s anchor. I believe it goes deeper—the anchor of the real is social welfare. If the stability of the currency is not maintained, the Brazilian people will suffer, and those responsible will pay a high price. This is why we can hope that some of the more outlandish proposals will actually be implemented,” concluded Armínio Fraga.

Otávio Dias is the content editor at the Fundação FHC. He is a political and international affairs journalist, a former correspondent for Folha de São Paulo in London, and former editor of the estadao.com.br website.

Translation: Todd Harkin, Harkin Translations