Indigenous Peoples Rights: An Obstacle to Development or Part of the National Wealth?

The bill that the Bolsonaro administration sent to the Brazilian National Congress to allow mining and other activities on indigenous lands must face not only the resistance of indigenous leaders, anthropologists, environmentalists and activists, but from the Congress itself (Rodrigo Maia, Speaker of the House, has already expressed he opposes the bill), the Federal Public Ministry, and even the Federal Supreme Court.

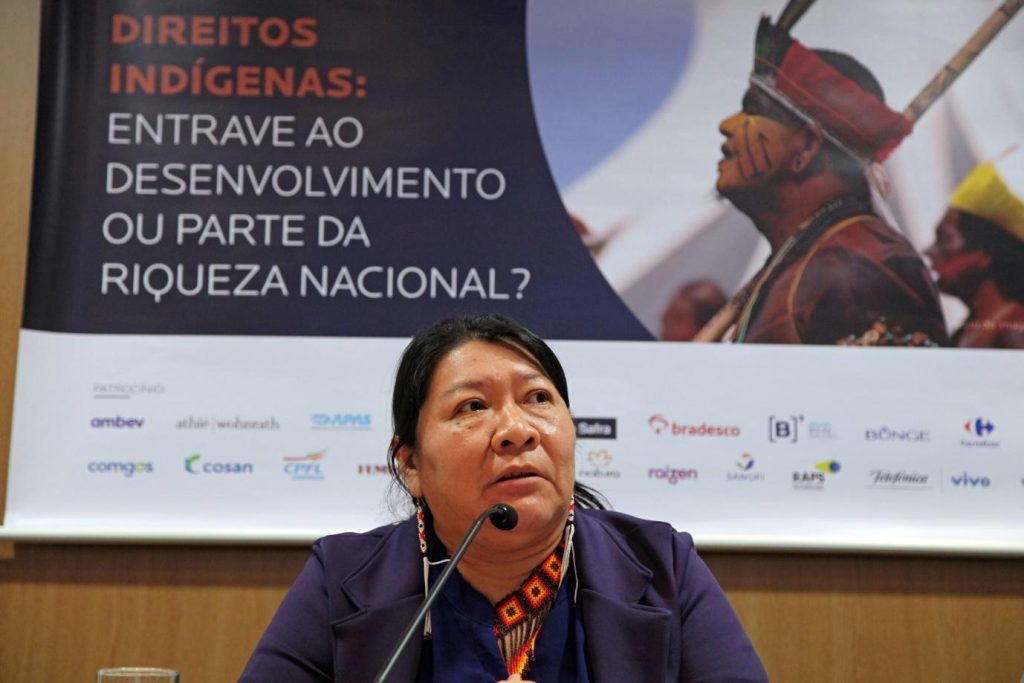

“I come here to state that the indigenous peoples of Brazil are a fundamental part of the national wealth. Our rights, clearly described in the Constitution of 1988, are not an obstacle to the development of the Amazon or the country. We want peace and tranquility to live according to our traditions. I say no to mining on indigenous lands.”

Joênia Wapichana, a lawyer, is the first indigenous Congresswoman, elected in 2018 by the Sustainability Network Party (Rede Sustentabilidade) in the state of Roraima, Brazil.

“As long as Congress does not approve a complementary law that regulates productive activities on indigenous lands, as determined by the Constitution and following the principles established by it, any mining in indigenous lands is unconstitutional.”

Mario Luiz Bonsaglia, Deputy Federal Prosecutor of Brazil, is an incumbent member of the 6th Chamber of the Federal Public Ministry, responsible for defending the rights of indigenous populations and traditional communities.

In a debate at the FHC Foundation, both Wapichana and Bonsaglia highlighted article 231 of the Brazilian Federal Constitution, which in paragraph 3 determines that “the use of water resources, including those with the potential for energy, research, and mining of mineral riches in indigenous lands can only be carried out with an authorization from the Brazilian National Congress, after a hearing with the affected communities, ensuring participation in the mining results, under the law.”

Paragraph 6 states: “(…) the exploitation of the natural wealth that exists in the soil, rivers, and lakes are null and void, with no legal effects, except in the cases relevant to the public interest of the country, according to the provisions of a complementary law (…).”

“What would be the relevant public interest for the country? The Constitution determines that we have original rights; they existed before the foundation of the Brazilian State. Indigenous lands are inalienable and unavailable, and the rights to them are not subject to a statute of limitations and are permanent. It is not about favor or ideology. It is the country’s duty to demarcate these lands and protect them,” stated Wapichana.

“It is not just now that indigenous lands are invaded by miners, loggers, and land grabbers. Indigenous peoples rights, although protected in the 1988 Constitution, in practice continue to be violated. Therefore, it is essential to regulate corporate mining and other productive activities in the reservations. One thing is certain: indigenous peoples must be at the center of the solution,” said geologist Elmer Prata Salomão, former president of the Brazilian Association of Mineral Exploration Companies (ABPM).

Biologist Ismael Nobre (Projeto Amazônia 4.0), environmentalist Márcio Santilli (Instituto Socioambiental), and agronomist Rodrigo Justus de Brito (Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock) also participated in the panel.

Wapichana: ‘We Want to be Heard and Suggest Alternatives’

According to the indigenous leader – who has a degree in law from the Federal University of Roraima, Brazil and a master’s degree from the University of Arizona (USA) – the constitutional rights of the indigenous peoples are under serious threat due to the imminence of the introduction of the bill by the Executive Branch, drafted without extensive public consultation from the indigenous communities across the country: “We want to really be heard and suggest viable and sustainable alternatives to mining and other activities that destroy the environment and our culture. So far, this has not happened. ”

The Federal Prosecutor recalled that Brazil ratified the 169th Convention of the International Labor Organization (ILO 169), on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent States, which determines that they should be consulted and freely participate in the adoption of measures related to the use, management, and conservation of their territories. “Consultations (with indigenous peoples) should be conducted in good faith and in an appropriate manner to obtain consent in relation to the proposed measures,” he said. The ILO Convention is the most up-to-date and comprehensive international instrument in respect to the living and working conditions of the indigenous peoples, and, being an international treaty ratified by the Brazilian State, it is binding.

For the Government, Native Indians Would not Have ‘Veto Power.’

According to a report published on January 11, 2020, by Brazilian newspaper “O Globo,” the bill that the government may introduce determines that it will be up to the Executive Branch to define the areas for the research and mining of mineral resources, hydrocarbons, and the use of water resources for the generation of electricity. Although it mentions the need to consult indigenous peoples, they would not have veto power: “The request for authorization may be forwarded [to Congress] with the opposing statement of the affected indigenous communities, as long as there is just cause,” cites one of the articles in the draft obtained by the newspaper.

According to Agência Brasil, in the opinion of President Jair Bolsonaro, the possibility of exploring mineral resources and carrying out other productive activities on demarcated lands will be like a Lei Áurea (that extinguished slavery in Brazil in 1888) for indigenous peoples. “We want indigenous peoples to be able to do on their land everything that a farmer, next door, can do on his. (…) Didn’t we have the Lei Áurea (the so-called Golden Law)? (…) I want to give a Lei Áurea to indigenous peoples,” he said. The Brazilian Head of State argues that there are indigenous leaders in favor of mining and other productive activities, as this would represent an influx of resources for their communities.

“Our constitutional rights are beautiful, but we are under enormous pressure because the current President of Brazil was elected with a speech strongly against the indigenous communities. In the 2018 campaign, he was in Roraima and promised to open the Raposa Serra do Sol Reserve for mining. He promised not only to paralyze but to revise the demarcations of indigenous lands and conservation units. He’s fulfilling his promise. He cut resources from the Ministry of the Environment and from agencies such as Brazil’s National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) and the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources (IBAMA), compromising the control and protection of our lands. The result is an increase in conflicts and violence,” criticized the Congresswoman.

Maia Promises to Shelve the Bill

Since 1996, Bill 1610, a proposal to regulate exploitation in indigenous lands presented by former senator Romero Jucá (of the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, or PMDB-Roraima state of Brazil), has been stalled in the Brazilian House of Representatives. In 2015, there was an unsuccessful attempt to move the bill forward. In 2019, the current administration announced that it would send a new bill to the Legislative Branch. In an interview with Globo News TV last November, the Speaker of the House, Rodrigo Maia from the Brazilian center-right Democratic Party from Rio de Janeiro (DEM-RJ), said he would shelve any indigenous land mining project that reaches the House.

“The existence of countless illegal mines is notorious, and the Brazilian Government has shown itself to be historically ineffective in protecting demarcated lands. All requests for research and exploration must be summarily rejected pending a specific law, duly approved by Congress, and approved by the Supreme Court. The Brazilian Federal Prosecution Service will fulfill its constitutional role in defending indigenous peoples rights,” warned Federal Prosecutor Bonsaglia.

“The rupturing of the dams in Mariana and Brumadinho shows that the country lacks the proper technical oversight and is unable to make inspections. In addition, towns where there are large mining projects hardly benefit from the wealth that is extracted. On the contrary. Numerous environmental and social problems arise, and those who benefit are mainly the project owners. Mineral exploration is not an adequate response to the true developmental needs of the indigenous peoples. There are other ways,” concluded Wapichana.

‘Illegal Mining is not Professional Mining,’ said Mr. Salomão

For Elmer Salomão, former president of the Brazilian Society of Geology, it is necessary to differentiate between illegal mining and business mining. The first would be carried out in a predatory manner, with environmental carelessness and no concern for the safety and health of the workers and regional inhabitants. The latter, when environmentally and socially responsible and according to well-defined rules and due inspection, would bring positive results for the environment and the surrounding community.

“Carajás Project is an example of how it is possible to explore mineral resources in the Amazon without destroying the forest and its biodiversity. Mineral extraction is concentrated in only 3% of the Carajás area, while 4,000 km² of national forest are permanently protected,” said the manager of GEOS Ltda. According to him, both the indigenous and other communities living in the Amazon (and other regions of the country) and Brazilian society as a whole should benefit from the wealth existing in the Brazilian subsoil, owned by the Union. “The legislation must make the various interests involved compatible, without harming indigenous peoples,” he said.

According to the expert, of the approximately 400 indigenous areas of the Brazilian Amazon, ten, at the most, would contain important minerals, but more research is needed to develop an adequate geological mapping of the region. “The indigenous areas are blind spots in terms of geological knowledge. There is no way to regulate what is unknown,” he explained.

Socio-Environmental Institute (Instituto Socioambiental, or ISA): One-Third of the Demarcated Land can be Reached

According to the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA), mineral exploration has the potential to affect almost one-third of the more than 700 indigenous reservations in the country. A survey performed by the NGO at the National Mining Agency (Agência Nacional de Mineração) identified more than 4,300 research or mining requests in 214 indigenous areas. A large part of these requests are from the 1980s and 1990s, before the demarcation of indigenous lands, and are intended to secure requestors with priority if the exploration is authorized.

“There is a distorted view that indigenous peoples live in poverty or even misery in their lands, when, in fact, many communities have reasonable living conditions and products to offer to the country and the world. It is important to get to know and stimulate the indigenous peoples economy, always respecting and protecting their ancient traditions,” said Márcio Santilli, founding partner of ISA, one of the most active NGOs in the Amazon.

“The social (and political) life of the indigenous village is also different from what we, whites, are used to. Community members usually sit in the center of the village, where everyone has the opportunity to listen and speak. Decisions are made collectively and must be taken seriously when defining which activities will be authorized in the reservations,” said Santilli, who participated in drafting the chapter on indigenous rights in the 1987-88 Constitutional Assembly and chaired FUNAI, Brazil’s National Indian Foundation.

Develop or Conserve? A False Dilemma

Biologist Ismael Nobre, co-responsible for Projeto Amazônia 4.0, alongside his brother, climatologist Carlos Nobre, argued that the way to improve the lives not only of indigenous populations but of other communities living in the region is to unite the “economy of the biodiversity with the possibilities created by the digital revolution and Industry 4.0.”

“Biodiversity + technology + creativity = sustainable development. This is the formula we propose for the Amazon. Add value to the region’s natural products, conduct remote training, facilitate communication and transportation to scale production, and marketing and accessing markets. Local communities must be the main actors in this process,” he suggested.

According to the scholar, currently, 18% of the total area of the Brazilian Amazon has been deforested or is degraded. “We will soon reach 25%, which can be the point of no return when the standing forest would no longer have the capacity to produce the amount of rain necessary to maintain itself. If we do not change the current course, in 2050, 50% of the forest will be gone,” he warned.

“Brazil’s main advantage over other countries is its biodiversity. Indigenous populations have been managing agroforestry systems for centuries, and they can help us become intelligent and responsible managers of this enormous asset that is the Amazon,” he concluded. To know more about Projeto Amazônia 4.0, read the English version of an article written by Carlos and Ismael Nobre and published by Cardoso Foundation last year.

Brazilian Confederation of Agriculture and Livestock (CNA): ‘There is Room for Everyone’

“Indigenous peoples rights are not an obstacle, and agribusiness does not need indigenous reservations to increase productivity. There are many degraded lands that can be recovered for agriculture and livestock, using more sustainable models of exploitation, without harming the forest,” said agronomist and lawyer Rodrigo Justus de Brito, a representative of the agricultural sector on the panel.

In early January, the newspaper “O Estado de S.Paulo” published a report on a farm the size of the town of São Paulo in Mato Grosso, which was degraded and in the red and, by integrating intensive livestock with soy planting, increased its food production 40 times without deforesting any trees. As a result, it started capturing CO₂ instead of emitting it, reversing its relationship with global warming.

“There is space for everything and everyone: indigenous communities and the productive sector, environmental preservation, and economic development,” said the senior advisor to the CNA.

Otávio Dias is a journalist who specializes in politics and international affairs. A former Folha de S. Paulo correspondent in London and editor of the news website estadao.com.br, he is currently the content editor at the Fernando Henrique Cardoso Foundation.

Portuguese to English translation by Melissa Harkin & Todd Harkin (Harkin Translations)