Assessment of one year of Emmanuel Macron’s presidency: ‘Breaking down taboos

“Macron has shown enormous audacity and the capacity to transgress and break down taboos, something which, in my opinion, France needed.”

Pascal Perrineau, professor of the Paris Institute of Political Studies (Sciences Po)

A little over a year after becoming France’s youngest ever president, at only 39, centrist Emmanuel Macron is carrying out reforms that affect essential sectors in French political, economic, social and cultural life at an accelerated rate. “It is still too early to evaluate the results, but no other French president has made so many reforms in one year”, said political scientist Pascal Perrineau, professor of the Paris Institute of Political Studies, known as Sciences Po, in the seminar “Assessment of 1 year of Emmanuel Macron’s presidency: is change underway?”, held in the Fundação FHC.

According to Perrineau, the reforms, aimed at vitalizing the country’s economy and aligning it with the rapid changes taking place worldwide, have led to protests and demonstrations by part of the diverse groups affected, but so far there is no movement solid enough to threaten the new president’s power and political majority. “I am not a clairvoyant and do not know what will happen in the coming years, but so far the social groups resistant to the changes have not coalesced into a political movement capable of articulating a more consistent opposition”, said the speaker, who from 1994 to 2013 headed the Political Research Center (CEVIPOF), one of the main political studies centers in France and in Europe.

Below there is a list of the reforms already undertaken or awaiting approval:

- Political life moralization law;

- Constitutional reforms, including decreasing the number of deputies in the French National Assembly;

- Labor reform (simplification of the Labor Code, to make it less rigid and more easily adaptable to the new reality of employment);

- Tax reform (further details below);

- Reform of university entrance, vocational and technical education (according to the speaker, the objective is to ensure young people are better prepared to enter the current labor market and to reduce unemployment among young adults, currently at over 20%);

- Reform of the unemployment insurance system (the range of benefits has been expanded while more rigorous controls have been introduced to prevent abuse);

- Reform of SNCF bylaws (public railway company, whose union is one of the strongest in the country).

‘President for the rich?’

During his campaign, Macron promised to reduce the tax burden as a means of boosting purchasing power for the middle and lower classes, on the one hand, and to release more funds for company investments, on the other. In recent months, the government has exempted 80% of the population from the “taxe d’habitation”, which is comparable to council tax, but caused controversy by revoking the Tax on Large Fortunes (IGF), “pleasing” both the right and the left.

By eliminating the wealth tax (IGF), the intention is to attract investors and discourage the flight of French millionaires to other countries (around 60,000 have fled since 2000, according to New World Wealth, based in South Africa). Accused by some critics of acting as “president for the wealthy”, Macron retorted: “We cannot create jobs without businessmen.” Read the report on this subject published in the newspaper O Estado de S.Paulo.

“I don’t know if the reforms will have the effect of accelerating the economy and reducing unemployment (9.5%), but the first signs indicate that investment is no longer paralyzed and is beginning to take off”, said Perrineau. Although it is the second largest economy in the European Union and the 5th largest worldwide, with high living standards, France underwent a period of quasi economic stagnation between 2012 and 2015 (growth from 0% to less than 1%) and only initiated a slow recovery from 2016. Expected growth for 2018 is around 2%.

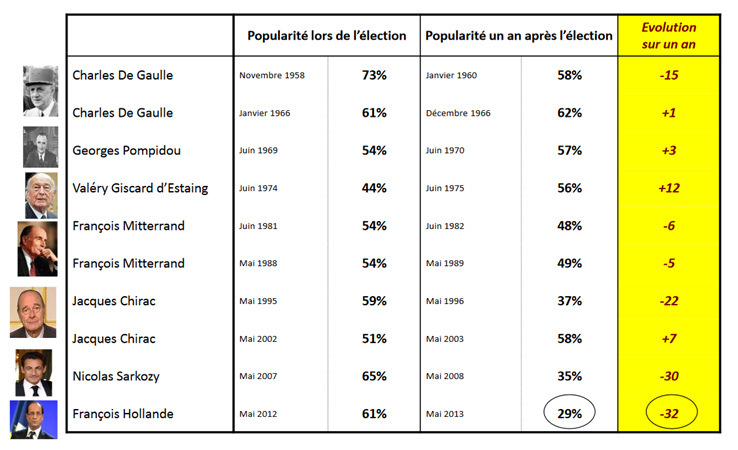

Support for Macron fluctuates

The table above shows the popularity of Macron’s predecessors (since Charles De Gaulle, at the end of the 1950s) on the day they were elected (percentage of votes in the second round) and one year after taking office. The socialist François Hollande (2012-2017) lost 32 points and had only 29% support after one year. Whereas republican Nicolas Sarkozy (2007-2012) lost 30 points, ending up with 35% support a year later.

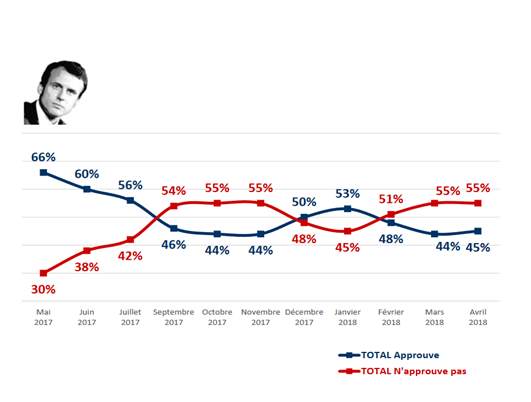

The survey above, conducted in April of this year, shows the evolution of support for the French president from May 2017, when he got 66% of the votes. In October, the percentage of supporters had dropped to 44%. In January (with the acceleration of the reforms) it climbed to 53%, but recently returned to 45%. The percentage of disapproval started at 30%, reached 55%, dropped to 45% and then returned to 55%. “There is a significant oscillation in relation to Macron, which is a cause for concern, but so far there has been no steady ongoing deterioration, as happened with Hollande, for example, who just went downhill all the way”, said the political scientist.

The same survey shows that for the French, none of his opponents would be doing as well as or better than Macron if they were at leading the government.

Reversal of pessimism

In spite of the many difficulties and uncertainties ahead, Pascal Perrineau stated that Macron’s surprising election had the power to reverse, at least momentarily, the trend towards self-depreciation, which he attributed to the “wounded Narcissism” of the French nation. “In recent years, the French, normally proud of their nation and their culture, had been very pessimistic about the country’s prospects, almost to the point of self-hatred. There are signs that this ‘disease’ is finally beginning to recede”, he claimed. In the survey, 39% of the French said that they believe that in four years the country’s situation will be better; for 32%, it will be the same and, for 29%, worse.

Broad parliamentary majority

If on the one hand the government is facing opposition on the part of French society, resistant to change, on the other it has a comfortable majority in the National Assembly. The parliamentary elections are held a few weeks after the presidential election and are heavily influenced by the winning candidate. The En Marche movement (founded by Macron in April 2016, a little over a year before the election which he won) presented a list of civil society candidates, half men and half women, with no prior political experience. In spite of the high abstention, the movement managed to elect 313 of the 577 deputies. “The immense majority of those elected are neophytes in politics and know very well who was responsible for their election as deputies”, he said.

France has a prime minister, but the president has broad powers, not only in relation to foreign policy but also in internal affairs. The president’s term of office is five years, with entitlement to one re-election. “This explains the rush to undertake these reforms so that they produce results before the 2022 elections”, said Perrineau.

Rupture in the left vs. right bipolarity

According to the Sciences Po professor, Macron was able to crystallize and personify a desire for political innovation that the French have harbored for years. “For a long time now, what we have seen is not just skepticism, but true hatred of the political class and the traditional party political institutions. At the same time, the French, who have a historical fixation for the spectacle of politics, had been showing a great deal of interest in the presidential election (in 2017). In Paris, if you want to liven up a dinner party all you need to do is talk about politics. How was this apparent paradox – mistrust vs. engagement – reflected in the election results?”, he asked.

In the first round (April 2017), around 22% of the electorate abstained, that is, they opted to “remain outside the system” while another 41% were protest votes, either for Marine Le Pen (ultra-right wing, who received 21% of the votes) or Jean-Luc Mélenchon (extreme-left wing, 20% of the votes). Only 26% voted for the candidates of the Socialist (Benoît Hamon) and Republican (François Fillon) parties, which had dominated French politics for decades. Neither of the two went forward to the second round.

“What few of us perceived was the arrival of innovation. If democracy doesn’t please us, why not try something else? Macron understood this desire for radical innovation and bet on creating a movement that ruptured the bipolar party system, which has dominated French politics for decades”, the political scientist explained. “When he announced that he would run, nobody believed he would be successful: ‘Ah, he is too small, he hasn’t got a party, he won’t get far’, they would say.

Macron launched his presidential bid independently of the traditional political system, knew how to take advantage of the opportunities that arose, gained strength and came in first place in the first round (24% of the votes) and then won the runoff against Le Pen (66% to 34%). “He showed how important it is to believe in oneself in politics”, said Perrineau.

‘New political divide’

According to the academic, the last election defined a new political divide in France. “During the campaign, Macron used to say that he was “neither left nor right’, but rather ‘left and right’ favorable to France having a bold and open mindset in relation to globalization. Whereas Marine Le Pen (who came second) said that she was ‘neither left nor right, but French’. This led to a new division, between a France more open to Europe and the world and a France more centered on itself”, he explained.

“The left and right are not dead, this dichotomy emerged in 1789 (French Revolution) and, since then, has been France’s major export. Except that it makes increasingly less sense in the face of complex challenges such as globalization, global warming, the construction of Europe and other contemporary questions”, the Sciences Po professor declared.

“Ever fearful of a vacuum, politics is experiencing a new ideological division, which I have been studying for over 20 years. It is a new split between social sectors that believe that we (the French) have more to gain from an economic, political, social and cultural opening to the world and those that think that it is time to return to profound economic, political and cultural protectionism”, he continued.

“In 1992, the majority of the French said yes to the Maastricht Treaty, the cornerstone of the European Union. But in the consultation on the elaboration of a European constitution in 2005, the majority opted out. On the two occasions there were ‘yeses’ from the right and the left and ‘nos’ from the left and the right. This was Macronism ahead of its time”, said the speaker. On May 7, 2017, the newly elected president commemorated his victory in front of the Louvre Museum, to the sound of the EU hymn and a combination of French and EU flags.

Also according to Perrineau, Macron initiated his campaign based on a political space closer to the center, but won over part of the left by defending liberal causes in the field of morality such as homosexual couples’ right to adopt children, and also gained a foothold with part of the right by promising (and undertaking) difficult reforms to reduce public spending and increase the competitiveness of the economy. “Today there is no doubt that he represents a new political reality with the power to shape the country’s future”, he claimed.

Horizontal in the campaign, vertical in power

Perrineau highlighted another surprising aspect of the Macron phenomenon; the desire, on the one hand, for a more horizontal, contemporaneous digital democracy and, on the other, for a verticalized political leadership that is imperial, “Jovian” in nature. “He called his political startup EM, after his initials. This was not done without a reason. While he loves to debate, discuss and is always willing to try to convince all comers, he makes it clear that there is no other chief besides him. He has in fact embodied presidential authority”, the speaker declared.

“This may seem contradictory, but research in Europe shows that while there is a demand for greater horizontality, such as respect for individual rights, there is also a demand for the exercise of authority”, the professor said.

“In politics, personality counts for a lot. Macron realized that there is the real body of the monarch (or the president) and the symbolic body. So far, he has been able to unify these two dimensions”, he concluded.

In the first year of his government, Macron received the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, at the Versailles Palace, with full pomp and circumstance, sending a clear signal that, like his powerful colleague in the Kremlin, he knows how to play with the “almost imperial” symbology of the role of president.

‘European dream’

On the external front, the major challenge is the relaunch of the European Union, in partnership with Germany, hindered however by the weakened position of the veteran German chancellor, Angela Merkel. In September 2017, Merkel won a fourth term as head of the largest European economy. However, she did not obtain a parliamentary majority and spent months negotiating an alliance, considered fragile, with the Social Democrats. “Macron always says that European skepticism is growing in all the countries on the continent because Europe has given up on its dreams of peace and prosperity and become too technocratic. He wants to revive these dreams”, said Perrineau.

He also wants to recover France’s position in the forefront of the world scene. Although he has established a friendly relationship with the North American president, Donald Trump, he has been heavily critical of the American’s isolationist policies, such as the withdrawal of the USA from the Paris Climate Agreement (2015) and unilateral trade measures. In a speech to the US Congress, he used the expression “Make our planet great again”, in counterpoint to Trump’s campaign slogan (“Make America great again”).

‘Will Brazilians also have political imagination?’

Pascal Perrineau avoided commenting on Brazilian politics but did say that here, as in France, traditional politics is suffering attrition and there is a strong desire for change. “We have very different political regimes, but could it be that the Brazilians, like the French one year ago, will vent their political imagination and elect a man or a woman capable of embodying this demand for innovation?”, he asked.

“What Pascal has been telling us about France applies to Brazil too, in spite of each country’s particularities. Just over five months from now, the Brazilians will take a decision that will define our chances for the near future and for the medium term”, said Fernando Henrique Cardoso, while thanking the speaker. “In Brazil, there is also a desire for renovation, but politics cannot be reinvented without being embodied in people. Also it is not enough just to have ideas. They need to be defended responsibly and implemented vigorously by a new leader, elected by the people. The election is the right moment for this new recommencement”, the former president concluded.

It is important to remember, as has already been said in the text above, that French society had been showing discontent in relation to the political system for a long time and it was only last year that it would appear to have found a possible response to that latent demand (only time will tell if Macron will in fact correspond to all these expectations). We cannot be naive in thinking that, in the case of Brazil, renovation is at hand, given that, at less than six months from the October elections, no political alternatives with a consistent discourse and political support have emerged.

Otávio Dias, journalist, is the content editor of the Fundação FHC. He was the Folha’s correspondent in London, editor of estadão.com.br and chief editor of the Brasil Post, a partnership between the Huffington Post and Grupo Abril.