“It is not just the economy, but identity! Many Europeans vote for nationalist and populist candidates mainly because they fear immigrants.”

Dominique Reynié, political scientist, is a professor at the Institute of Political Studies of Paris

“The Macron tree will not stop the populist and nationalist forest from continuing to grow and spread over the continent.”

Marc Lazar, historian, lectures at the same institution above, known as Sciences Po

The election of centrist Emmanuel Macron, aged just 39, as president of France in May this year prevented one of the main European nations and one of the six largest economies on the planet, a global symbol of democracy and freedom, from becoming a stronghold of xenophobic nationalism and populism, as well as avoiding the collapse of the European Union. However, the old continent is experiencing a “political epidemic” which is not going to disappear rapidly, with unpredictable consequences for Europe and the world.

“If France had fallen, the entire European system would have collapsed together with it. This was avoided, but in recent years populism and nationalism have been gaining ground as a major political force in Europe, a trend which has all the elements to continue”, said political scientist Dominique Reynié, lecturer at the Institute of Political Studies of Paris (Sciences Po), during this event at the Fundação FHC.

“Does Macron’s victory mean the end of populism in France and its weakening in Europe? Unfortunately no. There is a cultural broth nourishing populism and nationalism”, added Marc Lazar, who teaches history and political sociology at the same institution, one of the most highly respected in France.

See in the section Related Contents (to the right on this page) the results of recent elections in member-countries of the EU such as Austria, Holland, France and the Czech Republic, where parties with a nationalist and populist discourse received many votes and, in the case of the Czech Republic, won the election, albeit without a majority. The British decision to leave the EU, in a referendum held in June 2016 (Brexit), was also seen as a victory for nationalism and populism in the United Kingdom, as was Donald Trump’s election to the White House in November last year, which shows that the phenomenon is also in evidence on the other side of the Atlantic.

What are the Europeans afraid of?

According to Dominique Reynié, there is (so far) no conservative wave threatening the European lifestyle, which, in spite of the differences between the countries, is characterized by liberal customs and each person’s right to live as they want, as long as they do so within the law. According to the speaker, there is a reaction given the fear of a twofold degradation.

On the one hand, Europeans, mainly members of the middle class who live (or lived) on salaries from industry or agriculture, have the sensation that their economic well-being is under threat and that their children will not enjoy the same quality of life to which they are accustomed.

According to data gathered in the survey “Where is democracy going?”, based on 22,000 interviews in 26 countries, conducted between February and March 2017, and published by the Foundation for Political Innovation (Fondapol), a think tank directed by Reynié, 58% of European citizens (EU) believe that their descendants will have a worse future in their own countries than the current adult generation (see the results in the Related Contents section).

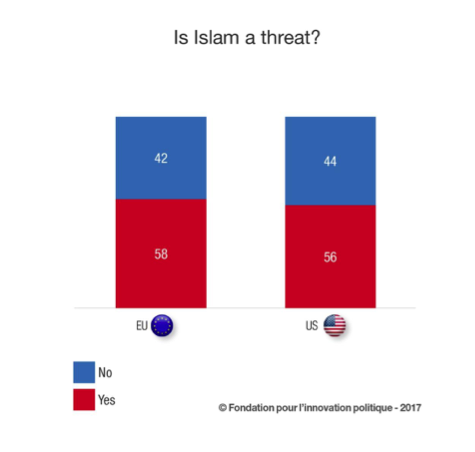

Furthermore, the increase in immigration, comprising illegal immigrants coming from the poorest countries in Africa, as well as refugees from the war in Syria and other countries in conflict, is seen by many as a threat to the European way of life and culture, of Christian origin (even though many Europeans do not practice and the majority of the states are secular). According to the Fondapol survey, 62% of EU citizens think that their lifestyle is threatened (in the USA, the percentage is 69%). For 58% of the Europeans, Islam is a threat (56%, among North Americans).

“Islam, ever more present on the streets of European cities, from the biggest to the smallest, represents a threat to the intimate feeling of those who previously felt protected at home and must now deal with an ethnic multiculturalism which they were not used to”, said Reynié. “Europe is currently experiencing a certain social chauvinism, the intimate desire to defend both a material and immaterial heritage. We want to perpetuate our way of life, to insulate ourselves in a kind of ‘socialism for whites’. It might be that in the future this phenomenon will lead to a conservative revolution (of habits), but for the time being this is not what is happening.”

In Eastern Europe (which remained isolated for many decades because of communism), the percentage of interviewees who see Islam as a threat is as high as 63% and, in Western Europe, 54%. Only 21% of Eastern Europeans see immigration as positive for their country, while 44% of Western Europeans believe this to be the case.

Merkel weakened

The difficulties the German chancellor, Angela Merkel, is facing to form a majority government, after a smaller victory than expected in the urns this year, confirms the thesis that Europe is experiencing a period of uncertainty. In the federal elections on September 24 , the AfD party (Alternative for Germany, with an anti-immigration, anti-EU and Islamaphobic discourse) came in third place, with 12.9% of the votes, and will have almost 90 seats in the Bundestag. This is the first time since the defeat of Hitler and the end of the Second World War that the extreme right will be represented in the German Parliament.

Merkel, whose party, the CDU (the center-right Christian Democrats), obtained 33% of the votes, has so far unsuccessfully been attempting to negotiate a coalition with other parties situated from the left to the center of the political spectrum. If she is unable to form a parliamentary majority, the chancellor, now in her fourth term of office, is threatening to call new elections. But there is concern that if a new vote is held, the extreme right could further strengthen its position.

France isolated?

After Macron’s significant victory, with 66% of the votes in the second round against the ultra-rightist Marine Le Pen (National Front), a number of analysts predicted that France and Germany would join forces to renew and extend European integration. After all, Merkel has always defended the EU, and Macron won the election with a pro-integration discourse. However, Merkel’s (relative) setback in the urns has frustrated this expectation, at least for the time being.

“With Merkel weakened, the race has intensified between the progression of populism and nationalism, on the one hand, and the construction of a Europe that ensures a future of peace and prosperity for all Europeans”, said Reynié. According to the political scientist, a Europe dominated by xenophobic nationalist governments “will tend to shut itself off to the world, which will no longer be the same”.

Right-wing nationalist parties already govern Hungary and Poland and, in October, a populist, euroskeptic billionaire won the election in the Czech Republic and may become the country’s next prime minister , although he did not get a majority.

Apocalyptic vision

Given the impasse in Germany, the challenge of leading the process of strengthening and renewing Europe is left mainly up to Macron. This would start with reforms in his own country, to make it more economically dynamic and capable of providing suitable responses to the expectations and needs of its citizens, discontent with the direction of politics, with the present and concerned about the future.

In the first round of the presidential election, around 50% of the French who took part in the process (78% of the electorate) voted for candidates critical of the political and economic system and the EU. The ‘anti-system’ candidates with the most votes were right-winger Marine Le Pen, who received 21.3% of the valid votes in the first round (34% in the second), and left-winger Jean-Luc Mélenchon, with 19.6% of the votes. “What did the two have in common? In addition to a negative view of European integration and globalization in general, both adopted an angry, anti-elitist discourse, seeking to personify the role of a leader who embodies the true aspirations of the people”, said Marc Lazar.

“They presented an apocalyptic view of Europe and the world, in which complex questions were reduced to a dichotomy restricted solely to yes and no, good and bad, us and them. By creating a new language, which encompassed the corporal, they put the other parties on the defensive”, the historian continued.

Although a member of the French intellectual and political elite (he was minister of Finance from 2014 to 2016), Macron himself (who received 24% of the votes in the first round) presented himself as an independent candidate, with criticisms of the country’s traditional political class. The biggest losers in the French election were precisely the two parties that had dominated politics in the country for decades: the Socialists (which, having been the most recent government, obtained only 6% of the votes) and the Republicans (20% of the votes, third place).

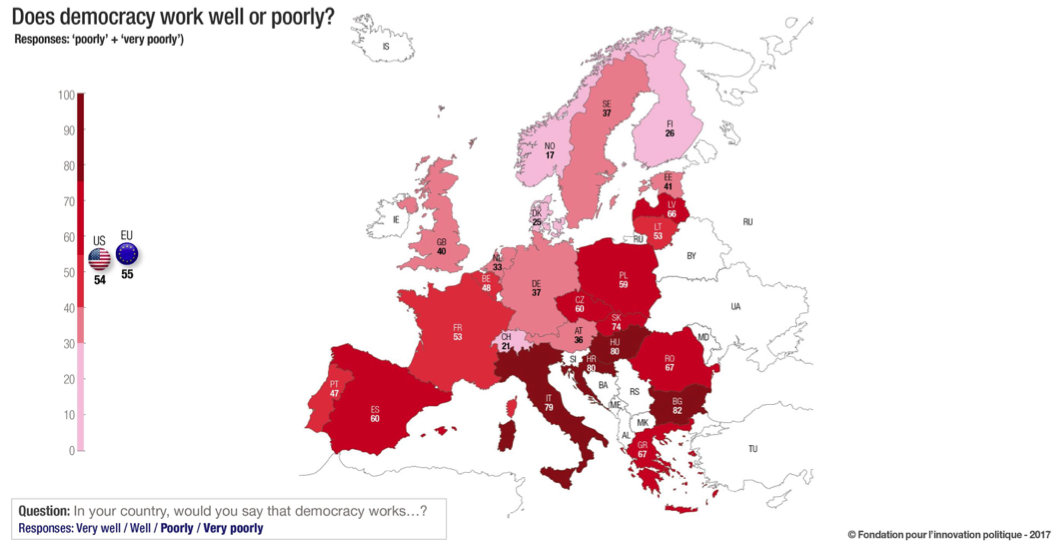

“The election results in France prove that something new and very important is happening in Europe, because it has been repeated in successive elections on the continent. Something is changing in the very conditions of democracy in Europe”, said Lazar. According to the survey presented, 55% of the interviewees in Europe think that democracy works poorly in their countries (in the USA, 54% have the same opinion).

Twofold challenge

Macron, therefore, faces a twofold challenge. Internally, he must advance in the solution of France’s economic and social problems, including unemployment and immigration, which for many people are interrelated. He also needs to find a more effective way to combat Islamic terrorism, whose most recent attacks have been carried out by (or involved the participation of) French or European citizens descended from families who migrated to France or other European countries from Africa, the Middle East or Asia, in some cases decades ago. Although born on European soil, these children of immigrants have become radicalized in recent years, participating in terrorist cells in Europe. They represent a minuscule proportion of the whole, but the consequences they provoke are enormous. For 61% of Europeans, immigration is harmful to the economy of their country and, for 56%, it increases the risk of terrorism.

Externally, the young French president needs to be successful in reducing the growing resistance to greater European integration, which includes complex issues such as a unified defense and security system, a common foreign and immigration policy and the survival of the treaty which permits the free circulation of people in Europe (Schengen Agreement), among others.

“Will Macron manage to prove that the state is capable of expressing and realizing people’s desires and needs?”, Dominique Reynié asked. “Before anything else, he needs to re-establish the French people’s confidence in politics, thus helping ensure that the political arena is not monopolized by the populists in Europe, which would represent a threat to liberal democracy, as is already happening in countries such as Hungary and Poland (governed by the more radical right wing).”

“If Macron is successful in his government, he could reduce the power of the populists in his country and consolidate France as leader in Europe (preferentially in conjunction with Germany). But, if he fails, what will come in his place?”, the political scientist asked. The French presidential mandate is five years, with entitlement to one consecutive re-election. In 2019, there will be elections for the European Union Parliament, which will serve as a thermometer to measure the populist and nationalistic fever on the old continent.

Promising start

Little more than six months after his election, Macron has scored some important victories. In June, his party, ‘En Marche!’, founded just over a year before, was victorious in the legislative elections (held after the presidential election), winning 308 of the 577 seats in the French National Assembly. The government bench comprises half men, half women, the majority of whom are representatives of civil society rather than traditional politicians.

With support from other parties, Macron has a base of up to 350 deputies, enabling him to approve controversial reforms, such as the labor bill signed in September, which boosted the flexibility of labor laws, in spite of the street protests organized by the unions, which are strong in the country.

Blind spot

But, according to the French political scientist, the key factor that remains unknown about the French leader is his position on immigration. “This is a blind spot in his government program, we do not know what he thinks about the question”, said Reynié.

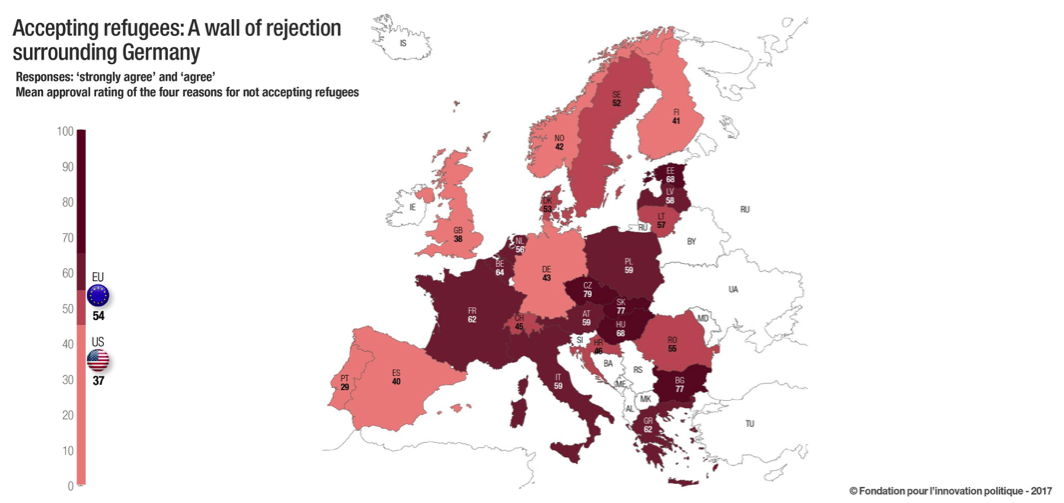

In fact, the immigration question was also one of the reasons for the electoral attrition suffered by Angela Merkel who, at the height of the European immigration crisis (2015), advocated keeping Germany’s doors open to immigration and providing war refugees with humanitarian treatment, as set forth in the UN Convention on the Status of Refugees. Initially, part of the German population supported her, but gradually resistance grew as the flow of immigrants from the Middle East to Germany increased, and Merkel was forced to establish more rigorous limits.

The chart below shows a wall of rejection of immigrants in the countries around Germany.

“Generally speaking, European governments, both on the right and the left, did not formulate public policies suitable for addressing immigration. It is as if the (more traditional) politicians did not want to touch on the problem. Macron was no different, although this issue was a crucial one in the last elections, when it was monopolized by the populist candidates. How will the president deal with this issue?”, he asked.

Resilient euro

Whereas the euro, in spite of the predictions that it was on its last legs during the debt crisis that affected some EU countries between 2009 and 2012, has consolidated its position as a mainstay of Europe, according to Reynié. This explains, in part, the defeat of the National Front candidate in France, and other European politicians who criticized the single currency in recent elections (in spite of the progressive strengthening of populism in the region). In March, the Dutch premier Mark Rutte (right-wing liberal) ended up beating the anti-EU candidate Geert Wilders, who at one point was leading the polls, in the first defeat of xenophobic populism in Europe since Brexit.

During the campaign, Le Pen reached the point of saying that the euro represented a “stab in the back” of the French and threatened to convoke a referendum on the maintenance of the currency if elected. But, between the first and second round, she changed her mind, saying the euro could coexist with a revived franc, drawing criticism.

“Marine Le Pen did not lose because she was a bad candidate or because she threatened the Fifth Republic (regime instituted by the current French constitution under the leadership of De Gaulle, in force since 1958). She was defeated because the Europeans, at the end of the day, feel more attached to the euro than to the principles that led to the creation of the EU. The euro today represents a point of resistance and a protection (against populist adventures). The true democratic capital of Europe is not Brussels (where the European Commission, the EU administrative arm, is located), but Frankfurt (headquarters of the European Central Bank). It is sad, but that is the case”, he said.

Further information:

Is there a global decline in democracy? Round table with Larry Diamond

A Europa em sua hora mais grave: 5 ameaças ao velho continente

Para onde vai a Europa? Na visão de José Manuel Durão Barroso

Europa: uma opinião de dentro e um olhar de fora

Watch Diálogo na Web, broadcast via YouTube, “2017 à vista: uma nova (des)ordem mundial”, with the journalists Patrícia Campos Mello and Jaime Spitzcovsky.

Otávio Dias is a journalist specialized in international affairs. He was the correspondent for the Folha in London, editor of estadão.com.br and chief editor of Brasil Post, a partnership between the Huffington Post and the Abril Group.